THROUGH THE VEIL & INTO THE CAVE: ANIS MOJGANI’S PLAYGROUND OF POETRY

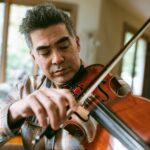

Written by Jennifer Perrine; Photographed by Frankie Tresser

Over the last two years, crowds have gathered outside Anis Mojgani’s studio in southeast Portland to listen to his poems ring out into the evening air. Though the sight of Oregon’s poet laureate leaning out his window, candlelit and gesturing buoyantly, became familiar to the people who filled the street for his Poems at Sunset out a Window events, the view from inside Mojgani’s studio is equally striking. Overlooking a school park where children jump in leaf piles, laughing loudly enough to be heard over the jazz record playing inside, Mojgani seems fueled by a childlike spirit. Though his writing has primarily focused on poetry—including five published collections—he’s also the author of The Pocketknife Bible, a “children’s picture book for adults,” and the children’s book Lifespans of a Rock, forthcoming in 2024.

He describes his interest in writing children’s books as part inquisitiveness, part happy accident. “Some of my favorite things in the world are the books that I read when I was ten,” says Mojgani. “That’s what my brain and my heart are curious about. And also, sometimes I’m sitting down to write, and I’m just making the space for what is on the other side of the veil that’s coming through. Like, through the veil I thought it was a giraffe, but in pulling it out, oh, it’s an elephant! Alright, well, I guess I’m putting an elephant into the world.”

His studio shelves and desk are stacked with children’s fiction, including books by Beverly Cleary, Maurice Sendak, E.B. White, and Edward Eager. “I love a middle grade book,” he says. “[It’s] the perfect length, and it’s the perfect balance of what is able to happen in a story.” Part of what Mojgani loves is the immediacy and simplicity of children’s stories. But part of his interest is also rooted in exploring his own relationship to his childhood in New Orleans. “There’s a tenderness that comes in engaging with books where the protagonists are young,” he says. “It allows me to just want all the good things for them. Ultimately, what I wish I had had for myself as a kid, I want for all kids. And that which I also had as a kid I want for all kids, because I had a very loving family that was so committed and rooted in story.”

Mojgani admits that, though his family introduced him to children’s verse, which he was “tickled by,” and books were prevalent in his house, he didn’t feel called to poetry until he neared adulthood. As a young person, Mojgani was fascinated by design and illustration. It wasn’t until he took a writing class in his senior year of high school that poetry found him. “That was really the first time I asked, ‘What does it mean to give language to what is inside of me?’ As a visual artist, […] it felt like somebody said, ‘You’re on the playground and you’ve been on these monkey bars this whole time. Here’s a slide if you want to go down.’”

In the nearly thirty years since this awakening to poetry, Mojgani has continued to explore writing alongside drawing and painting. He sometimes even thinks of his writing first as a visual medium. He points to a book about Black Mountain College, an education and arts experiment from the 1930s to 1950s. “I remember when I first saw that book on the shelf at Powell’s. The fonts in the book made me want to put text on paper. It wasn’t like, ‘Oh, this is beautiful language. Now I want to create beautiful language.’ It was like, ‘Oh, I love the way this ink looks on this page, the way these letters look on the page. I want to put letters on the page.’”

But Mojgani is equally influenced by poetry that exists off the page. “The summer before I went to college, I got introduced to poetry slams,” a form that “tricked people into listening to poems,” he says, by opening the mic to everyone. “You don’t have to have a degree. You don’t have to read a book. You don’t have to have taken a class. You could have just written that poem just now in the bathroom. Poetry really is for everybody, and it’s a thing that we get to use to figure ourselves out and connect with other people in sharing it.”