YOU DON’T KNOW UNTIL YOU TRY

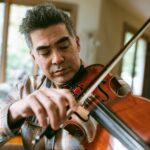

Written by Brian Benson; Photographed by Daniel Stark

When you meet Sankar Raman, in the lobby of a six-story building in Northwest Portland, he shakes your hand, deflects your compliments, and says, no, the honor is his, he’s been eager to meet you. You’re not sure why. You, after all, didn’t immigrate from a tiny town in India with little English and make a life as an American engineer; you didn’t found a thriving nonprofit dedicated to humanizing immigrants in response to skyrocketing xenophobia. You’re just a white guy with a notebook, a bike bag, and a sweaty forehead. Still, when Sankar says it’s an honor, you believe him.

The two of you end up on the fourth floor, in a bright room with floor-to-ceiling windows, through which you can just make out the southern tip of Forest Park, perched like a mohawk atop the city skyline. This building, according to a photographer you just met, was once full of artist studios, but has in recent years been colonized by Amazon. “Nowadays,” he says, “it’s all fulfillment.”

The two of you settle onto a couch. Sankar smiles at the view, then at you. His resting expression seems to be a warm, gentle smile, and you can’t help but respond in kind. You open your notebook and begin asking questions. You’re hoping to do for Sankar what he has done for so many others: tell a story, make a portrait, so all may know and see him as he’d like to be known and seen. As he talks, though, you notice something funny: he keeps pointing the conversation away from himself and toward other people. Like, for example, MrBeast.

“You know MrBeast?” he asks.

Somehow, you do not.

MrBeast, Sankar tells you, is a young white guy and the world’s most popular YouTuber. He makes loads of money filming videos of himself performing silly stunts and also engaging in high-visibility, ethically questionable philanthropy. (Later, you’ll look at his feed and find “I Paid a Real Assassin to Try to Kill Me” sitting just above “1,000 Blind People See for the First Time.”) “I wish I could have a conversation with him,” Sankar says. “He could teach me something. Millions of people follow him. But I look at my videos, which are, you know, survivor stories, some serious stuff, and I get 200 hits.”

Sankar pauses for a beat. Then says, “That’s what we are fighting against.”

For six years, through The Immigrant Story, the volunteer-run nonprofit he founded, Sankar has been fighting—against racist politicians and complicit media networks, and for the attention of an oft-distracted, apathetic public. Through profiles, pictures, podcasts, and live events, Sankar and his team give immigrants and refugees the chance to tell their stories in their own words. The idea, Sankar says, is to create a counter-narrative to xenophobia, one immigrant voice at a time. “How close can you get [the audience] to the story?” he wonders aloud. “Because when people get close, they are more apt to take social action—to do something without us even having to tell them.”

It all began, he tells you, in the wake of the 2016 election. Up to that point, Sankar hadn’t seen himself as a political person. After emigrating from India in 1980, he’d seen himself, mainly, as an Intel engineer, though he also dabbled in photography, which he fell in love with as a child. Then came a fateful trip back to India, where he took tons of photographs, only to develop them and discover, to his dismay, that he’d unwittingly adopted the colonial gaze of early idols like Margaret Bourke-White and Henri Cartier-Bresson: he’d gotten so many shots of strangers driving rickshaws and working in rice paddies, but few of his family simply talking, laughing, living. In the coming years, Sankar eschewed that exoticizing aesthetic—brown-skinned people shot from below or above, doing “traditional” things white westerners expected them to do—and developed a style all his own: he’d build rapport with his subjects, ask them questions, photograph them at eye level. He was still honing his style in late 2016, when a candidate campaigning on anti-immigrant rhetoric was elected president.