Pantoum for Kim Stafford1

Written by Kate Gray; Photographed by Daniel Stark

Every poet writes for different reasons, a boy’s hunger

to connect, stirred in sticks lit beside a forest stream

where he sat and listened to leaves and birdsongs, the sky

softened by rain and absence. Kim’s brother, Bret, was a bridge

connecting day and dream, their hands like sticks across streams

when they said—Good night, God bless you—and slept until Bret left

like rain, crashing leaves. Every year cherry trees bloom where Bret

with 300 classmates planted seedlings. Like blossoms, the memories return

of blessings brothers say before bed—Sweet dreams—the trees a tribute

more alive than any book a brother writes for a brother.2 Kim weaves

for hundreds of students a spell, to make stories bloom, to pause

time, when writing, their poems connecting one to another, bridging

not fixing lives, long or short.3 A poet, Kim tells them, can’t weave words

for money, so they’re free to write as they please, and nobody really understands

how poems succeed. But poems do connect people, he says, so poets are free

to write the meaning learned outside school and books, on streets. Poetry

may be a luxury, no money to be made, but each poem may save

somebody a little at a time, waking them to each moment, the privilege

of being present.4 Meaning made outside school rises with power

from the subconscious. A poem is a place to put that gift, set it down.5

As Oregon Poet Laureate, Kim had the privilege of waking early to write

for people in solitary places, the immigrant mom who “stepped into her dream,”

the prisoner whose pain rose and filled a poem where the story got set down and

pounded into gold, and all Kim’s relations “so they may be strengthened.”6

For those his poems serve, Oregon’s strong mothers, immigrants, “I have a weakness,”

he says. You need only two things to write a poem—abundance,

the gold of joy or pain, and a beginning place where poets can pound a path

to compassion.7 Every poem is a passport for connection—a way

to serve boys too shy to stream their thoughts, who spill over with joy or sadness—

A poem is a place for those who listen to leaves and birdsongs—to walk under

a sky soft with longing—for strangers to connect by looking across a fire

into the eyes of those hungry for stories. Kim helps us find our common ground.

[1] The contemporary use of the traditional pantoum form in this poem underscores the importance of Kim Stafford’s position as William Stafford’s son and a poet wholly himself, an Oregon Poet Laureate descended from an Oregon Poet Laureate. In a pantoum, every 2nd and 4th lines become the 1st and 3rd lines in the following stanza. Here, the repetition with variation is meant to reflect the echoes in the Staffords’ work and their indelible mark upon the region.

[2] Kim shared a bedroom with his older brother, Bret, in their childhood home in Lake Oswego, Oregon. Before they went to sleep, Bret would ask, “Shall we make a bridge?” and Kim would stretch his arms from his bed to Bret’s and Bret would crawl across. Then Bret would make a bridge for Kim to crawl across. They would recite a blessing/poem before going to sleep. Kim wrote 100 Tricks Every Boy Can Do: How My Brother Disappeared years after his brother, Bret, took his own life when he was 40. The loss of his brother set Kim adrift, and telling the story was important for Kim and his sisters and their families.

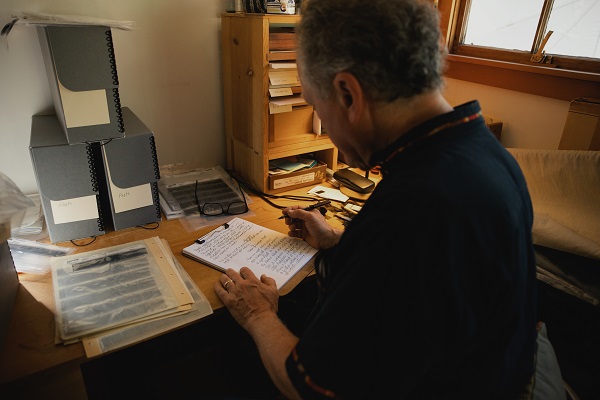

[3] Kim has donated his personal archive to Lewis & Clark College, where he taught for 40 years. Recently, while delivering boxes of notebooks and memorabilia, he discovered a box in which he had thrown the starts of poems he had written while students were writing. A foundational tenet of the Northwest Writing Institute, which Kim founded, is the democratic principle of writing together: everyone is equal when writing rough drafts. Kim commented that, from those scraps, poems rose. Dr. Hannah Crummé, the college archivist, said that Kim’s archive and William Stafford’s archive “speak to each other.”

[4] These three things Kim tells every group of students he meets. With these insights, he works against the stereotypes often transmitted in school: that poems are mysterious and incomprehensible and should, therefore, not be approached; that published writers can get rich; and that poetry doesn’t matter.

[5] Kim’s son once said that using tools does not distinguish us as human, but looking across the fire into someone’s eyes and telling stories, that exchange of gifts is what makes us human. “Poetry creates a zone of safety for thought,” Kim says, “Because [a poem] is short, you can give yourself to it.”

[6] As Oregon Poet Laureate from 2018-2020, Kim visited many small towns in Oregon and gave away a collection of poems he had written for local people and their places. He learned from Elizabeth Woody, Oregon Poet Laureate from 2016-18, that a poem should not just perch in a book but should go forth to serve people. The lines quoted here are from those poems and for the people he met. In meeting with Native Oregonians, he learned the blessing made for “all my relations,” a phrase he had started using without knowing it was meant to include ancestors and descendants. Kim admits that he comes from strong people—in particular, his mother, who grew up in Nebraska and had the use of only one arm, would hurl herself into a silo of grain as a child and “swim.”

[7] As founder and director of the Northwest Writing Institute at Lewis & Clark College, Kim created a model to teach teachers how to incorporate writing into every classroom and use writing to foster compassion and cooperation. During Kim’s tenure, the Institute developed interdisciplinary and inspiring curricula that promoted writing as a tool of innovation and peace-making, the kind of teaching both parents practiced.