Music for the Joyful Earthling

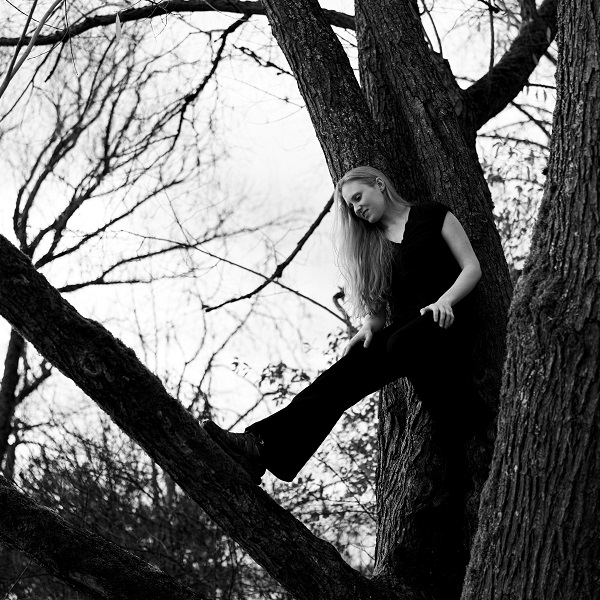

Written by Emma Marris; Photographed by Andrew Wallner

Gabriella Smith felt guilty about making music as the world was burning. How could she justify playing with sound and pattern—exploring the percussive possibilities of cellos, juddering a violin bow staccato across its strings—while climate change threatened to destroy ecosystems and cultures? “It felt so selfish and inconsequential compared to, you know, wanting to solve the climate crisis.”

It isn’t like she wasn’t doing anything to help. Gabriella has been involved in various kinds of climate action for a long time. She got her start at age twelve, volunteering for a songbird research project in Point Reyes, California. As she tells me about her feelings of guilt, we are standing in a little forest, wet with Seattle rain, where Gabriella, now thirty-one, volunteers, working with her hands on ecosystem restoration—planting, weeding, tending. “I’m not leading it or anything,” she explains. “I just sign up online and show up, like anybody can do.” Through a group called the Green Seattle Partnership, Gabriella and thousands of other volunteers have helped this forest in Magnuson Park and other green spaces around the city thrive. I admire a young madrona, with its characteristic creamy warm orange bark. It is one of my favorite Pacific Northwest trees.

I appreciate Gabriella’s work here in part because I grew up with this park. As a teenager, I would come here to swim or attend outdoor concerts. I saw Pearl Jam play here in 1992. The only plants I remember from those days were endless tangles of blackberries and close-cropped lawns. This was before the park’s ecological rebirth. It was also before I grew up to be an environmental journalist and writer, before I started really falling in love with other species, even as I chronicled how climate change and other human actions could threaten them.

Gabriella played violin as a youth, then studied composition at Curtis Institute of Music in Philadelphia from 2009-2013. An early success was 2015’s “Carrot Revolution,” a gristly, weird, exuberant string quartet composition. But for years, her climate work was separate from her calling as a classical composer. One of her first explicitly environmental works was 2018’s Requiem, written for eight singers and string quartet. In the piece, the traditional Latin requiem Mass text is replaced with the Latin names of all the species that have gone extinct in the last 100 years. That Requiem takes twenty-five minutes to perform makes me deeply sad.

Sadness is an inescapable emotion when confronting environmental loss and change. I feel like I’ve back-stroked through oceans of sadness in my career. But while Gabriella agrees that “we need to feel our grief in order to do the work,” she has increasingly tried to capture the joy that many also feel when working on climate issues: the thrill of determination, the sense of community one builds with one’s compatriots, whether you are filing legal briefs, marching in the streets, or planting madronas. This is where the Venn diagram of Gabriella’s music and my writing overlap: we are so over doom and gloom.

Continue Reading

Gabriella says her journey for the last fifteen years has been about trying to answer one question: “How can I still be of use in the fight for a livable future while being a musician?” Her preliminary answer—preliminary because the journey is by no means over and her answers are by no means final—is to make music about the joy of climate work.

Her pieces capture the sounds and feelings of being in beautiful natural places—often seashores, from swooping notes that sound like sinking in deep ocean waters to adorable seafoam bubble pops she produces with her mouth. After all, the flip side to the agony of losing beloved places is the love we bear for them in the first place.

Some of the joy emerges as a kind of boisterous physicality, sounds unquestionably made by physical instruments, often stretched to their limits. One can hear the grippy texture of horsehair on the strings, or the pleasingly organic hollow wooden knock of the cello as it is playfully battered by the cellist. These sounds are born of the pure “fun of making music.” Gabriella’s pleasure in playing with sonic possibilities goes back to her youth, to hours spent “finding all these weird sounds on my instrument when I was maybe supposed to be practicing Bach.”

But it also relates to her current theme, she says. “Music is fun; working on climate solutions can also be really fun.”

Along with this immersive three-dimensionality, there is a wild enthusiasm for life in Gabriella’s music that comes through so strongly to my ears that it can emotionally shuck me like an oyster. But as often as her pieces spiral upward into a wide open sky of possibility, they can also explode into a confetti of chaos. Disorder doesn’t scare her. “Chaos,” she says, “can also be beautiful.”

In 1973, violinist David Harrington started a string quartet in Seattle inspired by George Crumb’s Black Angels, a tense, harrowing composition about the Vietnam War. The Kronos Quartet continues to commission music about contemporary crises. For their fiftieth anniversary celebration, Gabriella has composed a thirty-five-minute piece called Keep Going, which incorporates the voices of professional activists and everyday people working on climate change, all of whom Gabriella personally interviewed. “It sort of goes back and forth between scoring an audio documentary and the voices becoming part of the music itself,” she says. The first voice listeners hear comes from a student who worked here in Magnuson Park, with Gabriella, restoring the forest. The last movement features a collage of isolated syllables of speech, sewn together until it sounds like singing.

Gabriella and I walk from the forest to the shore of Lake Washington. It is late November, and it is very cold. Seagulls are calling. We sit on a bench and watch two women in swimsuits jump in together, issuing little cries of discomfort and triumph. “I want to help people feel invited into the climate movement, because I think a lot of people don’t feel invited,” Gabriella says. “We don’t only need scientists, we need everybody. We need everybody in every aspect of society to be using what they’re good at and what they like doing to help solve the climate crisis, right?” Action, she says, whether it be planting trees, lobbying congress, protesting, or making art, is the only real way to feel hope.

I am almost embarrassed to ask Gabriella my next question because she is, after all, a serious classical composer. But I feel like what she is describing is a kind of soundtrack for doing the work. I ask her if this description feels right. “I like that,” she says.

In the weeks that follow, I test out playing Gabriella’s oeuvre as a soundtrack to my own work. The folk-pop vibes of “Bard of a Wasteland” from the Lost Coast album make a great propulsive score to draft a book proposal to. But the Keep Going demo doesn’t quite work as music to write to. Its unexpected twists, its narrative voices, its scritchy-scratchy hopeful strings, its frogs—like so much of Gabriella’s work, it refuses to recede into the background. That insistence is the point. Like Gabriella and the millions of people who care about climate change, it demands your attention, invites you in.