YOU WON’T BELIEVE YOUR EYES

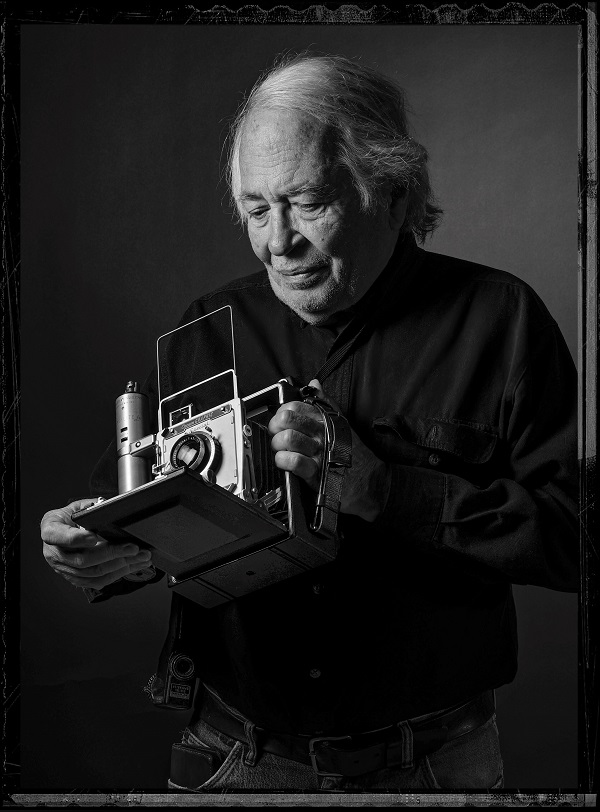

Written by Joe Wilkins; Photographed by Jim Lommasson

Joe Cantrell and I are sitting in a busy coffee shop in Old Town Sherwood—mid-morning light at the windows, the clink of saucers and cups punctuating our conversation about photography, the inherent wholeness of all things, and seeing beyond our acculturated vision of the world—when Cantrell stops, mid-sentence, and with a quickness that belies his advancing years, is up and out the door. Seconds later, he shuffles back in with a coiled length of rope. Every millimeter, he says, represents one year. “That—” he points near the cut end, to the first of a series of concentric red marks on the rope, “is the flooding of Celilo Falls. That’s the Treaty of 1855. That’s Lewis and Clark. And here’s the first white man to set foot in the Pacific Northwest.” At this point, we’re only a matter of a few inches down the rope. “All the rest,” Cantrell says, letting the scratchy weight of the rope fall into my hands and spreading his own arms wide, “most of fifty feet—it’d unroll right onto the street!—is the existence of the Natives on this land.”

Joe Cantrell isn’t an activist or historian. He’s a photographer, someone concerned with seeing the world as clearly and coherently as possible. But over a long, full life (you’d find his birth millimeters down the rope from the flooding of Celilo Falls) Cantrell has discovered that sometimes simply seeing is a far harder and worthier project than we imagine it to be.

Joe Cantrell is Cherokee, originally from Tahlequah, Oklahoma. As a boy, he used to track animals through the woods, a practice that was all about seeing what wasn’t there, noticing patterns of absence. He took a photography class in high school. One day at home, toying with his school-issued camera, a lacewing landed on his finger. He quickly snapped a picture. The resulting photograph would change the direction of Cantrell’s life. He thought he’d seen the lacewing. He hadn’t. Not really. Looking at the developed photograph, he could see even the light streaming between the veins of its wings.

After high school, like so many young men from rural spaces, especially young Native men, Cantrell enlisted. His father had been career military, and many people Cantrell respected still believed in the necessity of the Vietnam War. Even after the horror of his first tour, Cantrell volunteered for another. “I couldn’t believe what I’d seen,” he says. “I wanted to make sure. That time, I saw immediately that what was happening to the Vietnamese was what had happened to us, to the Cherokee. Except this time I was the bad guy.”

After his time in the military was up, Cantrell spent sixteen years as a photojournalist in Asia, documenting lives very different from his own—and very much the same. “I’m trying,” Cantrell says, of all his work, “to make a coherent whole out of a world that we see as independent parts.”

Looking for a change, Cantrell and a girlfriend touched down on the West Coast, in Portland, Oregon. Restless and untethered and full of hope, they drove a used Toyota 9,000 miles around the country looking for the best place to live. They came full circle. Portland was the place. Cantrell worked as a photojournalist again, but after his relationship fell apart, and after he was awarded sole custody of their three-year-old daughter, he took a series of what he calls “regular jobs”—even if, as he admits, he wasn’t very good at them—just to keep food on the table.

His daughter is now grown and thriving in the tech industry in LA. And in recognition of the continued effects of his service on his health, the VA finally awarded Cantrell a pension, which has in recent years allowed him to focus solely on his vocation, his photography. Now, he does photojournalist work for arts organizations—most notably, Oregon ArtsWatch—and fine art photography, which has been shown at Portland Center Stage and studios across Portland.