Elements of Style

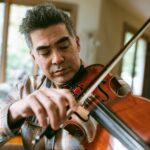

Written by Gabriel Urza; Photographed by Iris Hu

Fabric:

It starts with the fabric. The substance, the thing that is cut. For Komi Jean Pierre Nugloze, maybe the fabric is his body, his life.

I meet Komi Jean Pierre at N’Kossi Couture and Fashion, his storefront in Pioneer Place in downtown Portland. He is tall and lean and handsome, a black collared shirt under white sport coat striped a vibrant black and purple. We are surrounded by West African fabrics: the iridescent, intricate florals of Dutch waxed cotton and geometrically patterned Java batik, striped dan fani from Burkina Faso, Kente for weddings from Ghana, tie and dye from Guinea. There is a dimensionality to the clothes at N’Kossi. You want to touch them, to feel the rough braille of a raw tweed or the smoothness of a wedding fabric from Mali.

Or maybe the fabric is the first act of Komi Jean Pierre’s life, back in Togo before he moved to Portland a decade ago. In Togo, fabric was a part of life—one that Komi Jean Pierre remembers as slower, more social. His first foray into fashion when he was fifteen, dressing two friends before going out for the night. His four years of design school in Lomé, where he learned to sew and measure, how to cut the billowing necks and sleeves of traditional women’s clothing. His first paid work, sewing school uniforms and clothing for special events for people on the military base where he lived.

This is the fabric from which Komi Jean Pierre Nugloze has cut a life.

Measurements:

Komi Jean Pierre puts on a tidy black apron before showing me his workshop, tucked into a back corner of his storefront. There are two sewing machines spooled with colored threads: pink and white and burgundy, purple and red and taupe.

The people that come to Komi Jean Pierre for clothes are African Americans looking for something to remind them of their cultural roots, or they are Africans living in the US who want to wear something from home. Or they are people who traveled to West Africa and fell in love with the electric, unique patterns of the region. They are people dressing for a special night, a formal event or a wedding. Or they are drag performers looking for something arresting, unforgettable. More than anything, Komi Jean Pierre wants his clothing to reflect each client, who they are, and how they want to be seen.

Komi Jean Pierre doesn’t typically use patterns. Instead, there’s something organic to his process. When a client comes to him, they decide together on the piece to be made—a jacket, or a dress, or something in between. After they work together to select a fabric, Komi Jean Pierre sets to work. He uses a thin, curved piece of wood that he carried from Togo to create the shape of an outfit. Instead of the straight line of a ruler, the règle captures the curves and contours of a client’s body, which he translates to fabric.

“Right now, people want something special,” Komi Jean Pierre tells me. “They want a tailor or designer to take your measurements, to discuss the design with you.” This is the thing you can’t buy at a big-box department store: a shared experience, working with a designer to make something original, an individual piece for an individual person. It’s a way not only to value Komi Jean Pierre as an artist, but for the client to value themselves.

Shears:

On his worktable in the back of N’Kossi is a large pair of black-handled shears that Komi Jean Pierre uses to carve the patterns of his clothing, to rearrange blank fabric to conform to the shape of his client’s body and bring two-dimensional material to life. He creates his own story from each blank canvas, stitching disparate pieces into a perfect tapestry.