An Art of Sea and Time

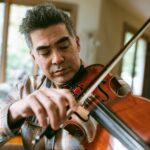

Written by Armin Tolentino; Photographed by Laura Dart

You can be forgiven if you don’t know where the salt in your cupboard comes from. When you’re at the supermarket, perhaps you don’t select salt with the same care you use to select tomatoes or salmon, assessing quality, color, or responsible means of harvest and cultivation. But there was a time in our history when humans considered salt as precious as jewels and lustrous metals; when nations waged war over access to this mineral; when revolutions fomented against its taxation, and salt was reserved for communion with gods.

Ben Jacobsen knows. He’s not judging you if the teaspoon for your recipe comes from a Morton canister. But as the founder of Jacobsen Salt Co., the first company to handcraft salt in Oregon since Lewis and Clark’s expedition in 1805, he does recognize that there’s such a thing as great salt, that there’s an art to its harvest, and that it’s worth paying more attention to this indispensable ingredient we’ve likely taken for granted.

For years, Jacobsen himself didn’t care about salt. When he earned his undergraduate degree in economic geography at the University of Washington, his passions included competitive cycling, travel, and the outdoors. But when he moved to Denmark to earn his MBA at Copenhagen Business School, he was introduced to high quality sea salt. It seemed an extravagance for a grad student, until he experienced firsthand how superior artisanal salt was to its commodity counterpart. He was hooked.

After moving back to Portland, scouring local kitchen shops and grocery stores, he was surprised to find none of the finishing salt was locally sourced. “I became really curious: was there a reason that great salt wasn’t being made here? People had kind of overlooked the magic of the Pacific Northwest.” That curiosity, and his love of the coast, drove him to study traditional salt making techniques and, in 2011, to found a salt company of his own.

Despite its extensive coastline, Oregon’s conditions are not ideal for sea salt production. High rainfall dilutes salinity and the many rivers that rage into the Pacific generate turbidity that would gum up any filtration system quickly. Add to that agricultural runoff, intense weather, and sheer cliffs impeding access, and you understand better the trial and error it took Jacobsen to find the right locale to source his salt.

He tested twenty-seven sites between southern Oregon to the northwestern tip of Washington. Netarts Bay was the runaway winner. Compared to other coastal locations, Netarts Bay is a sensory deprivation tank. It has higher salinity since it’s only fed by the mild trickle of creeks. Its shallow water is calm, protected from the rampaging Pacific by a natural sea wall in the Cape Lookout State Park Spit. And it’s home to ten million oysters—a living first line of water filtration since the Mesozoic. In his first year, Jacobsen was hand-pumping 275 gallons from Netarts Bay into barrels he transported via U-Haul to Portland for processing. In late 2013, he took over a former oyster farm nestled in the southern crook of the bay and began producing his salt right on the shoreline where it was sourced.

The process of hand-harvesting salt is the culinary equivalent of erasure poetry, subtraction rather than addition. Or, like the apocryphal quote attributed to Michelangelo on how he created his masterpiece David—I simply carved away everything that was not David—Ben and team take thousands of gallons of bay water and simply remove everything that is not salt.

Continue Reading

But simply does not mean easily. “We could make salt in a day,” Jacobsen concedes. “But we couldn’t make our salt in a day.” Their process takes heat, patience, and an artist’s intuition to recognize when the salt is ready for harvest.

At slack tide, when Netarts is at its fullest, Ben’s company pumps the oyster-filtered water into holding tanks where it’s further filtered through reverse osmosis, damming back anything bigger than a single micron, which ensures micro-plastics aren’t infiltrating their product.

This water undergoes two weeks of careful boiling and evaporation. Rush this process and your salt is tainted with calcium and magnesium, making it bitter and harsh on the tongue. Too much heat and the crystals refuse to unite into the beautiful flakes that the New York Times, in the first year of the company’s existence, described as “so pitch-perfect it tastes like it’s from a centuries-old European workshop instead of a start-up in the Pacific Northwest.”

But with patience and attention, the water thickens into brine and the once invisible sodium and chloride ions coalesce on the surface as translucent pyramids. These crystals, coaxed from the water, become so large they break the surface tension and drift to the bottom of the evaporation pans. Seeing this, you can imagine the same wonder Neolithic salt makers must have experienced when crystals seemed to materialize out of nothing, alchemical magic divined from the sea.

Jacobsen’s crew carefully shovels the salt out of the tanks like clean, fluffy snow. After four days of dehydration, salt makers pour them into barrels. They tinkle like chimes, so dry and light are the crystals.

This final product, Jacobsen Pure Flake Sea Salt, has been used by some of the most beloved and visionary restaurants in Portland, including Salt and Straw, Le Pigeon, and Kann. But for Jacobsen, it’s just as important that home cooks get to enjoy something a little special. “We’re sensory creatures,” he explains. “We respond to taste, texture, sight, sound, touch.” When you use Jacobsen salt, yes you’re tasting this incredibly clean, briny flavor from such an elementally pure product. But you’re also savoring the visual of bright white, delicate flakes adorning your dish. Textural crunch adds contrast and even a sonic facet to the experience. There’s a sense of ritual finishing a dish with a sprinkle of salt flakes, like blessing a meal.

Since starting his company, Jacobsen’s relationship with food has evolved. He’s now so much more cognizant of its sources, of the relationship and critical balance between humans, plants, animals, agriculture, watersheds, mountains, weather. When he talks about his journey, gratitude imbues every word. Gratitude and wonder. He knows his company’s efforts are nothing without Netarts, this estuary nuzzled in fog and firs. “The quality of our salt is directly correlated to the health of Netarts Bay as it is today.”

That word today is key. He’s aware of the enormity of time and space when he talks about the ocean and the salt within it. “We’re really just harnessing a very small sliver of what the bay provides us at that time. An infinitely small slice of time and place.” Salt making becomes an expression of Jacobsen’s overall philosophy of interconnectedness. Just as his salt has the merroir of the Pacific Northwest etched in its crystals, he believes each of us carries the spirit of this region inside us. “We’re very much a part of our environment in the Pacific Northwest. We get outside, we look up. We sink into the seasons.”

The ocean bears salt because of erosion on land. Rainwater chips the mountains bit by bit into creeks and rivers, which carry sediments downstream, into the sea, on and on, for eons. Jacobsen offers in his salt a tiny piece of the very earth we stand on—another blessing, that the everyday act of eating connects us to this place we call home.