The Art of Practice

Written by Armin Tolentino; Photographed by Laura Dart

There’s a memory from Jeremy Okai Davis’s childhood that still echoes within him: his uncle, the late Walter Davis, an NBA All-Star, was visiting family back in North Carolina, shooting hoops with his young nephew. Jeremy missed a shot and it was time to head inside, but Walter dropped a piece of wisdom that Jeremy would never let go of: “You can’t walk away on a missed shot.”

Basketball was a central part of the Davis household, and for much of his youth, one of Jeremy’s deepest passions, along with art. He’s since channeled his energies from basketball to painting, but he’s applied everything he learned from the court to the canvas.

The Practice

Growing up in Charlotte, Davis’s life as an athlete and an artist were always two distinct worlds; but within, the two passions fed each other. He developed a work ethic in the gym that drives his artistic determination today. His studio is a Tuff Shed in his backyard; the proximity to his house, maybe twelve steps door to door, can be a challenge. How do you motivate yourself to show up and work, when you might not have ideas, when you might be bored, when the living room couch sounds much more welcoming than the Tuff Shed at night?

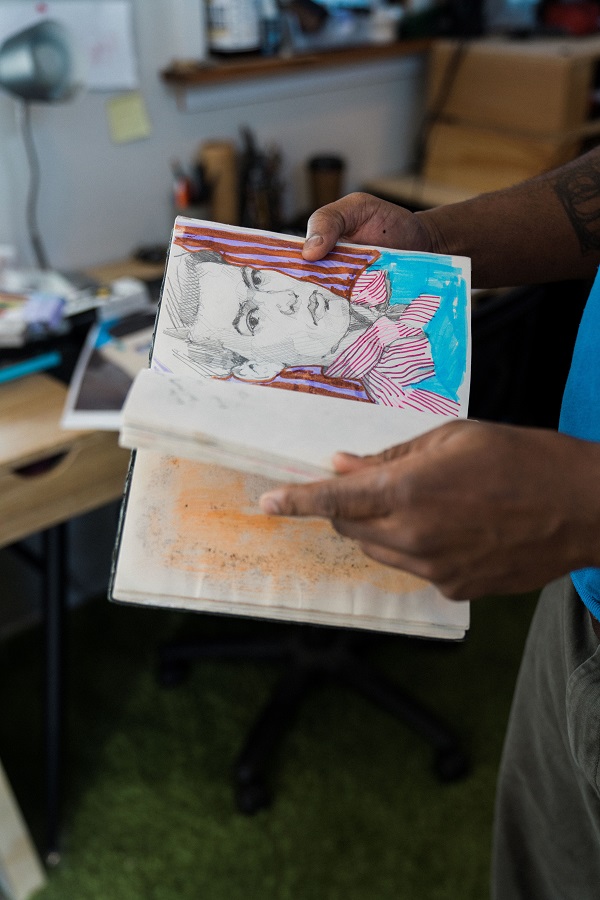

Davis talks about artistic preparation like an elite athlete. He quotes his uncle’s advice and tries every day to “make the shot in the studio.” Through sixteen years of constant practice since moving to Portland, he’s developed an idiosyncratic style of portraiture, in the vein of pointillism, where each brushstroke of color retains its distinct independence instead of melting into homogeny. Step back, and the subject’s face blends into gorgeous coherence. Step closer, and the viewer sees the many pebbles of hues that materialize when we pay attention at this more intimate proximity. With only a few colors, Davis is able to recreate the entire spectrum of human skin tone, but also peppers in pops of green and blue and hot pink, which help bring out, he says, “the eccentricities of people.”

It’s all about showing up: “Just getting in the studio, trying things and playing around. You’re flexing a muscle. Trying to see how it feels. That’s the workout.”

The Game

If basketball and painting have in common a necessary commitment to practice, the ultimate performance for an athlete and an artist look very different. Success in sports is so measurable…there’s literally a score. How does Davis, after all that exertion and the late nights in the studio, know whether his work, ultimately, was successful?

Engagement, he tells me. Jeremy’s game day is now the opening night of his exhibitions. And while his work has been displayed at dozens of prestigious locations, including the Portland Art Museum, the Washington Convention Center, and the Multnomah Courthouse, he doesn’t measure success by the number of people who show up. It’s not enough for his paintings to be simply attractive. He expects the portraits to inspire conversations, spark curiosity, and sow new knowledge, especially for viewers outside of the fine arts world. The son of two educators, perhaps it’s no surprise that Davis’s mission as an artist has evolved in this direction: through the still medium of portraiture, he seeks to reanimate the vibrant histories and accomplishments of Black athletes, leaders, culture bearers, and trailblazers.

In 2018, the Port of Portland displayed an exhibition of Jeremy’s work along Concourse A of the Portland International Airport. Some traveling parents were so compelled by his work, they reached out to him. “Your painting stopped my daughter in her tracks,” they said. “Here’s what it meant to her.” These moments of engagement are precious to Davis. That a child, in the frenzy of an airport between gate and baggage claim, could be so taken by works of art. That her family paused and listened to what she and the paintings were trying to share. That they were moved to share with him in turn. Fittingly, this exhibit was called More Education, fourteen pieces that reflect Davis’s childhood influences and loved ones: a painting of his father holding his infant brother, with the words COACH emblazoned in block letters beneath; the cover of James Baldwin’s The Fire Next Time.