Keep the Joy Intact

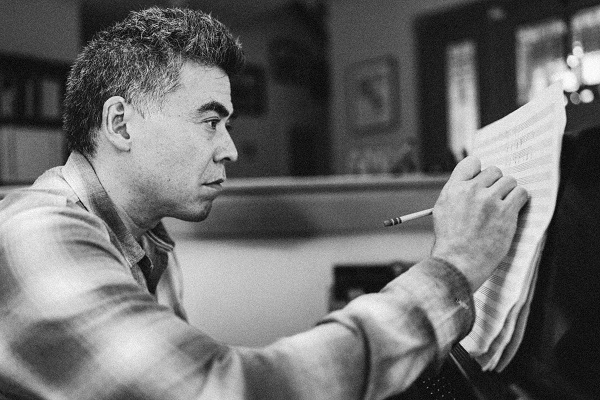

Written by Daniel Tam-Claiborne; Photographed by Iris Hu

Long before Kenji Bunch established himself as one of America’s most influential and prolific composers, he came to classical music in a way familiar to many young Asian Americans. “For a long time, I’ve tried to come up with any other reason, something somehow more intelligent,” he said. “But what I’ve realized is that I saw classical music as my calling largely because it made my parents happy.”

Bunch, who was born and raised in Portland, grew up in a biracial household with two parents he describes as “deeply committed parents but deeply wounded people.” His dad grew up impoverished, the son of a sheep rancher in Eastern Oregon. After enlisting in the Navy, he used the GI Bill to become the first person in his family to go to college.

“Classical music for him represented an aspirational, unattainable marker of status that he figured was beyond his reach,” Bunch said. “It was a great source of pride that he was providing for my brother and me to take private lessons. We were constantly reminded of that.”

Bunch’s mother was born in 1938 in Japan; her earliest memories were of diving into ditches during air bomb raids. Though she grew up a world apart from Bunch’s father, she shared the notion that Western classical music represented a kind of hope. “She saw it as the ultimate affirmation of the human spirit and resilience,” Bunch said.

Bunch began playing piano and violin at age five, and switched to viola at twelve. “I was never a prodigy by any means, but once I switched to the viola, things clicked, and I got serious about it.” His talent for the instrument was evident, but his desire to stick with it was borne of equal parts joy and obligation. Although Bunch didn’t know how much his parents really understood the music, he could sense that hearing him perform made them happy in a way that he rarely saw growing up.

Consciously or not, Bunch took it upon himself to do the very thing his parents couldn’t: decode classical music. At The Juilliard School, where he was admitted to study viola performance, Bunch began taking music theory classes. He had always been interested in composers like Béla Bartók, and quickly found himself spending more time writing music than practicing it. When he graduated in 1997, he became the first student at Juilliard to receive dual Masters of Music degrees in viola and composition.

“I never felt the need to choose one over the other: they’ve both helped each other. I’m a better violist from composing and I’m certainly a better composer for being a performer.”

That duality is reflected in Bunch’s approach to musical styles. He is a hybrid performer, amalgamating traditional forms and European-based classical music; his unique compositional voice is said to mirror the diversity of global influence on American culture, often incorporating elements of hip hop, jazz, bluegrass, and funk, to critical acclaim. He has worked with a wide-ranging who’s-who of prominent artists, including Ornette Coleman, Lenny Kravitz, Sigourney Weaver, and Stephen Sondheim, and his music has been performed on six continents and by over seventy American orchestras. “As a performer myself, I got to the point where I could decide to try and continue to become the best classical violist I could, or I could try to do a bunch of other different things,” Bunch said. “That seemed like a more interesting journey.”

For Bunch, this inclination can also be traced back to his parents’ influence. His mom’s record collection was heavy on Beethoven and Western opera; his dad’s had a lot of swing-era jazz and old Broadway musicals. “As a kid, I never really distinguished what was considered more serious,” Bunch said. “I was interested by all of it.” He remembers attending a lot of concerts growing up, and though he loved the spectacle and the music, he admits that he also spent at least half of that time really bored. When he started composing, he wanted to write what he wished he could experience in a concert. “I tried to imagine if this music could travel through time and do things that were anachronistic to that time and place.”