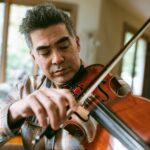

SPEED, POWER, PLAY: TAKESHI YONEZAWA’S LIFELIKE LEATHER ART

Written by Jennifer Perrine; Photographed by Katy Weaver

Translation assistance provided by Yuko Hardy

When encountering Takeshi “Yone” Yonezawa’s “Determination”—a life-size sculpture of a red-tailed hawk constructed entirely from leather—you might feel awe at the bird’s broad wingspan dwarfing everything else in the room, or you might be spellbound by the precision of its plumage, from the gradients of brown bars on its back to its coppery tail feathers. You might be struck by Yone’s skillfulness, tenacity, and reverence for this creature—and you’d be right. What you might not imagine, though, is that Yone describes the 2,000 hours he devoted to creating this project as “fun.”

“I love the challenge,” says Yone. “People say to me, ‘You have patience.’ No, I have passion. People think, ‘I wouldn’t want to do this,’ but I’m really having fun.”

Yone’s affection for leather began in grade school, when he played baseball and developed an appreciation for the material of the gloves and cleats he used every day. As a senior in high school, he worked in a Native American jewelry shop that also sold deerskin bags.

Although he began working with leather as a hobby in his apartment in Japan in 2001, for the next decade his primary artform was playing guitar. “I wanted to be a professional musician until I was thirty,” says Yone. “Ten years is not a short time! But the last band I was in was composed of top-level musicians, and I had to recognize that there was a gap between their technique and my own.”

As his music career was winding down, Yone chose to focus on leatherworking instead. “I really appreciate the time I spent with music because I kind of feel like I made a mistake with it. I didn’t do enough. So, with leather, I was determined to do well.”

In 2014, as Yone was making that transition, he married, and told his wife, “I can go anywhere you want, but I need my leather studio.” Their move to Portland, Oregon, brought immense change to Yone’s work.

“I used to carve using Sheridan style tooling,” says Yone. This practice, developed in Wyoming as part of saddle-making tradition, includes carving floral patterns in a flowing yet orderly fashion. Yone trained in this method in Japan, where the majority of leatherworkers practice Sheridan style. When he started entering his work in leather shows in the U.S., though, he was disappointed with the reactions to his art. “‘Your tooling is clean,’ they said. ‘You have skill.’ I could have been happy about that, but I felt something wasn’t quite right. I realized that originality is the key. It has to be one of a kind.”

Shortly after, Yone had the opportunity to carve a design for a magazine cover. He based his design on Sheridan style but chose a magnolia pattern inspired by Kamakura-bori, a form of traditional Japanese wood carving Yone describes as “powerful.” “I wanted to put this kind of power into leather.”

Rather than working from a drawing and tracing his designs, Yone carves immediately onto the leather, improvising as needed. “It’s not always perfect,” he says, “but I always like to show speed and power, and direct carving is best for that. If I draw on paper, it looks more organized. It looks clean, but not exciting.”

As Yone became more accomplished at carving, he also began to explore leather sculpture. He honored the Native American leatherwork he first encountered as a teenager by recreating a Fort Belknap Reservation warbonnet—a headdress including over 3,000 beads, 640 leather horsehair strands, and over 100 eagle feathers—entirely from leather. The project entailed months of research in which Yone studied the construction of warbonnets and the cultural and ceremonial significance of their different elements.

That project was preparation for his sculpture of the red-tailed hawk, which was eleven years in the making.

Yone first had the idea for sculpting a leather raptor when he lived in Japan, where he loved watching black kites. When he first attempted to create a bird from leather, he quickly realized he needed to focus on precision. “How big is the head? And what’s the eye color, the beak size? I didn’t know any of that.”