Pink Martini’s America

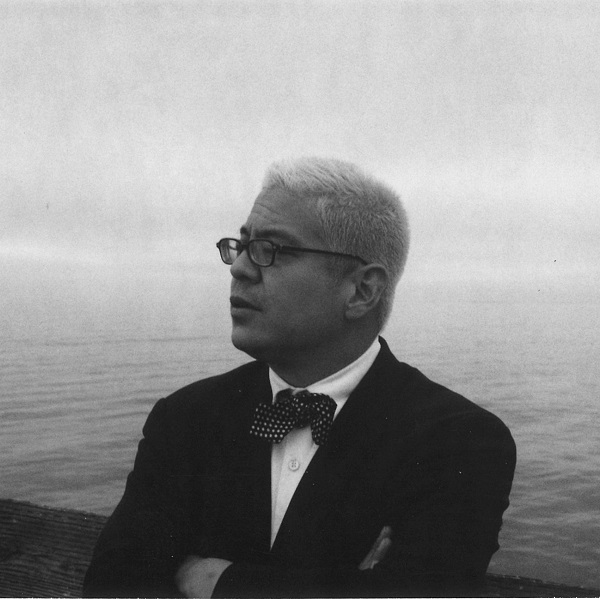

Written by Daniel Tam-Claiborne; photos provided by the artist

Thomas Lauderdale never intended to become a professional musician.

This may be surprising, considering that Lauderdale is best-known as the charismatic band leader of Portland’s self-described “little orchestra,” Pink Martini. With twelve albums featuring songs in twenty-five languages, Pink Martini’s music deftly fuses classical, jazz, and old-fashioned pop to create an eclectic and timeless aesthetic that is entirely their own. Now entering its 30th year, Pink Martini has sold millions of albums, and tours their world-renowned repertoire 150 days out of the year, across the globe. “If the United Nations had a house band in 1962,” Lauderdale has said, “hopefully we’d be that band.”

But Lauderdale had no ambitions of joining a band, let alone being the ringleader of one. Though he’d studied piano since the age of six, in rural Indiana, and soloed with the Oregon Symphony in Portland at age thirteen (after his family’s move to Oregon, he began studying with Sylvia Killman, his teacher and mentor for forty years), Lauderdale quickly concluded that he didn’t want to be a classical concert pianist and didn’t want to go to conservatory. His interest was in politics.

Lauderdale was student body president at U.S. Grant High School; later, he worked for Portland Mayor Bud Clark in the Office of International Relations, and with City Commissioner Gretchen Kafoury on Portland’s first civil rights ordinance. He remained active in politics as an undergraduate at Harvard, and after graduating with a degree in History and Literature in 1992, returned to Portland with the dream of one day becoming Mayor.

That trajectory changed in 1994, when Lauderdale was confronted with Measure 13, a proposed anti-gay rights amendment to the Oregon constitution. Lauderdale organized a week of protests in opposition to the bill, and—determined to bring some “fun” to the decidedly underwhelming political fundraising landscape—invited the Del Rubio Triplets to Portland to campaign. (“I had just seen them—three gals, three guitars, wearing mini-skirts and booties, somewhere between the ages of seventy and eighty, warbling covers of ‘Walk Like An Egyptian’ and ‘Whip It’—on Peewee Herman’s Christmas Special,” he recalled.) He capped the week off with a public concert at Cinema 21. When the opening band canceled last-minute, Lauderdale donned a Betsey Johnson cocktail dress, enlisted a singer, a bass player, and a bongo boy…and Pink Martini was born.

Soon, Pink Martini found themselves as the house band for political fundraising, championing civil rights, education, the environment, affordable housing, and music education in the schools.

While they don’t play overtly political events today, there remains a quiet diplomacy at the heart of the band’s ethos. “I used to make more huge political statements from the stage, but I just don’t do that now. Things are divided enough,” Lauderdale said. “We’re very much an American band, but we spend a lot of time abroad and therefore have the incredible diplomatic opportunity to represent a broader, more inclusive America.”

Pink Martini’s America is cross-generational, cross-cultural, cross-political. Lauderdale calls music one of the “very few intergenerational activities in our country,” and the band prides itself on explicitly appealing to conservatives and liberals alike.

“A third of our audience voted for Donald Trump,” Lauderdale told me, somewhat incredulously. As Ari Shapiro—NPR host and regular guest artist with Pink Martini—wrote, “It’s hard to view someone as an enemy when you’re dancing and clapping along to their songs.”

These days, Lauderdale is more interested in finding commonality where others might seek to find difference. “At the end of the day, we all have to live together. We have to find ways to talk with each other, and be civil and kind.”

Continue Reading

Lauderdale has always had a unique ability to unite unlikely audiences. As an undergrad at Harvard, he was known as the “cruise director,” throwing waltzes with live orchestras and ice sculptures, disco masquerades with gigantic pineapples on wheels, midnight swimming parties, and operating a Tuesday night coffeehouse called Café Mardi, where jazz legend and classmate Joshua Redman played regularly. He brings the same verve as a soloist with numerous orchestras and ensembles, including the Oregon Symphony, the Seattle Symphony, the Portland Youth Philharmonic, Chamber Music Northwest, and Oregon Ballet Theatre. And although his solo work serves a very real purpose—“it forces me to practice and be more deliberate”—Lauderdale much prefers collaborating with other musicians.

Few bands ever make it to a decade together, let alone three. Lauderdale credits the band’s lasting endurance to their diverse cast, something of an anomaly in the music business. “One way Thomas has kept the band fresh,” Shapiro writes, “is pulling other interesting people into his menagerie, like a bird weaving shiny ribbons into his nest.”

The band’s core membership has grown to twelve (plus “a never-ending parade of guest artists”), including Lauderdale’s longtime friend and Harvard classmate, lead singer China Forbes. “It’s great to have a posse,” Lauderdale said. “The musicians bring their disparate influences and interests. Some come from the symphonic classical world, others are hardcore jazz players, others bring Afro-Cuban and Brazilian rhythms to the table. If we were four people, we would have imploded a long, long time ago.”

Pink Martini and Lauderdale are often touted as “Oregon’s musical ambassadors to the world.” It’s a fitting title for Lauderdale, who credits Portland as the only place Pink Martini’s story could have unfolded. “In 1994, Portland was podunk and didn’t care,” Lauderdale said. “The whole vibe of the city was My Own Private Idaho. Rents were cheap, so there was a lot of room to be creative and not go broke.”

Lauderdale has a remarkable talent for bringing people together on and off the stage. His home—a historic building in Portland’s financial district, which he shares with his partner, classical pianist Hunter Noack—is a 9,000-square-foot monument to togetherness that Portland Monthly described as “one of the city’s most important cultural hubs.” In addition to dinners, gatherings and sing-a-longs for the many local organizations on whose board he serves, he hosts an annual holiday party, complete with caroling, a forty-foot tree, and “arguably the most eclectic and influential gathering of Portlanders to be found.”

When I talked to Lauderdale in February, his project for the day was taking the tree down. He had invited over 500 people to his home on Christmas Day, including the kids of his parent friends—over thirty of them under ten years old. They had commandeered a nook in Lauderdale’s loft and christened it “Star Camp,” complete with its own rules. “If I was a kid getting to go to a party with artsy teenagers and octogenarians, I would think it was so cool,” Lauderdale said.

But outside of a Pink Martini concert, those opportunities are rare. More, even, than a musician, Lauderdale considers himself a historian. He is an ardent collector—“there’s a fine line between hoarding and collecting,” he laughs—of everything from antiques to cakes. He showed me his library, where he keeps volumes of Life and Look and Ebony and Playboy, hundreds of books of Pacific Northwest literature and Oregon Black history, and Oregon journals dating back to the 1900s.

“I like rescuing history that is buried,” he said. “I just think that the past is so well-built—better written, smarter—and there’s a lot to learn from it. I have a great amount of respect for that.” Notably, many of Pink Martini’s primary collaborators are over eighty.

“We’re going in the opposite direction of American pop,” he laughed. “It’s more like Lawrence Welk on acid or The Muppet Show crossed with Wild Kingdom.” Though Lauderdale never set out to be band leader, it’s so clear that he was born for this: to entertain, to inspire, to serve as a bridge across myriad divides. “I mean, it’s old-fashioned. But for the younger generation that doesn’t know about the past? It’s all new to them.”